What happens when a dream becomes too powerful, so powerful that it bleeds into waking life and reshapes reality itself? Not the dreams of individuals, but the dreams of societies, cultures, and entire civilizations. We live in a time where collective imagination often tilts toward despair, suspicion, and catastrophe. Wars spread like wildfires, economies wobble, artificial intelligence feeds back our biases until paranoia blooms, and the leftovers of religious thought put us in a vulnerable position as to how we process everything going on around us. This is not just politics, economics, or technology. It is what we might call collective spiritual psychosis: a breakdown in how we imagine and interpret the fabric of existence itself.

Collective imagination as a force of reality

The human mind has always been a tool for world-building. Myths, rituals, and stories are the architecture of civilizations. When shared, imagination becomes a scaffolding that entire societies inhabit. Yet imagination is a double-edged sword. A person who dreams of prosperity may create it. A person who dream of apocalypse may manifest collapse. Jung spoke of the collective unconscious as a reservoir of symbols and archetypes shaping human experience. When those archetypes skew toward destruction, the Flood, the Fire, the End Times, they do not remain confined to dream-space. They leak outward. They shape laws, wars, markets, and technologies.

In this sense, reality is never entirely objective. It is scaffolded by imagination. And when imagination curdles, reality can curdle with it.

The dream turning nightmarish

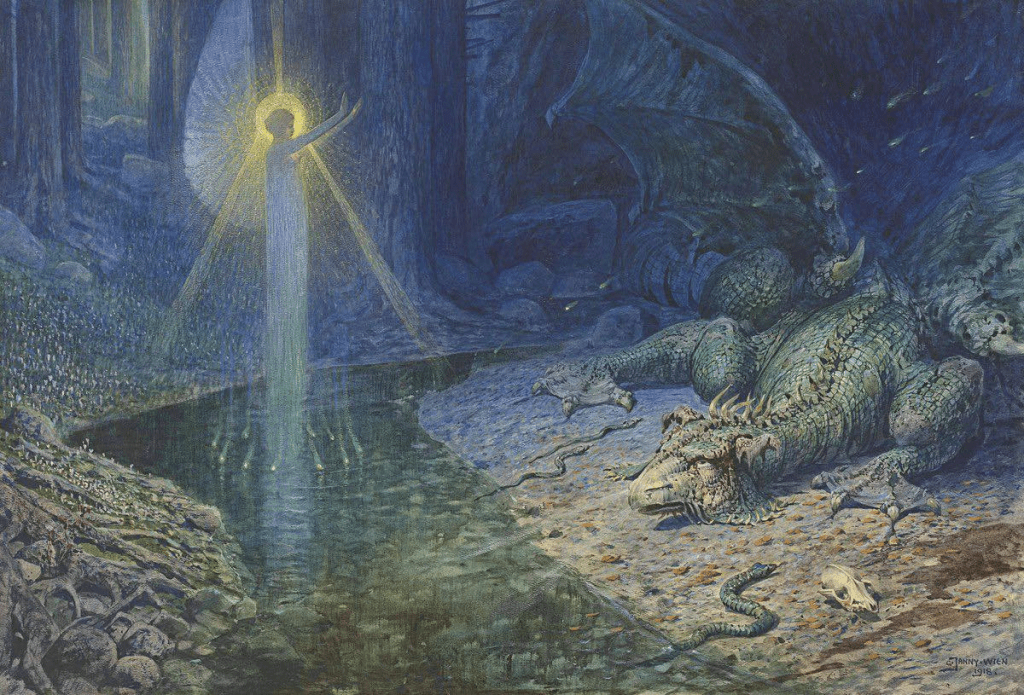

Fear is the most primal form of imagination. It takes the unknown and fills it with monsters. Fear-driven imagination is not passive. It guides action. Armies are mobilized, borders sealed, surveillance intensified, economies militarized. Fear shrinks possibility down to a single tunnel: survival. But ironically, fear-driven survival strategies often accelerate collapse.

Today, we collectively dream in shadows: ecological collapse, nuclear war, technological enslavement. These nightmares are amplified by media and reinforced through algorithms. Entire nations, entire generations, find themselves imagining the worst while acting in ways that make the worst more likely. This cycle is not just political dysfunction. It is a form of mass psychosis rooted in the spiritual dimension of human thought.

Religion as amplifier of spiritual psychosis

Religion once offered hope, redemption, and symbolic structure. But when filtered through fear, religion itself becomes a psychotic dream. Apocalyptic cults, doomsday prophets, and religiously framed wars show how sacred symbols can be hijacked to reinforce despair.

The irony is that sacred traditions, at their root, are tools for transcending fear. Mystical currents within Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, or Buddhism speak of union, liberation, and peace. Yet what rises to the surface in times of instability are the darkest interpretations: wrathful gods, holy wars, prophecies of destruction. When these motifs dominate the collective imagination, they feed into political realities. Armies march not only with guns, but with stories of divine vengeance.

Thus, what might have been a path to spiritual health instead mutates into spiritual psychosis: collective delusion masquerading as divine will.

AI as the new oracle of despair

Technology has always extended the human psyche outward: printing press, radio, television. But artificial intelligence represents something unprecedented, a mirror that not only reflects but amplifies our inner states. Feed it paranoia, it magnifies paranoia. Feed it bias, it sharpens bias. Feed it despair, it offers infinite variations of despair.

This creates what we might call algorithmic psychosis, a feedback loop where collective fears are reified by machines and then fed back to us as truth. The result is an acceleration of fragmentation. Reality itself feels unstable because the shared symbolic order, the consensus reality, is constantly being fractured and reassembled by algorithmic dreams that no one truly controls.

If Jung’s collective unconscious once expressed itself in myth and folklore, today it expresses itself in data patterns and machine learning models. The danger is that AI is not neutral. It inherits and magnifies the darkness we already project.

Economic instability as spiritual destabilization

Economies are not purely material. They are symbolic systems of trust and imagination. A dollar is only valuable because we collectively imagine it to be. When faith in that system erodes, the collapse is not just financial. It is spiritual. People lose not only their livelihoods, but their sense of orientation in reality itself.

The 21st century is defined by financial shocks, recessions, inflation, and inequality. Each new destabilization strengthens the psychic undertow. Anxiety about the future is not only about bills or jobs. It is about the collapse of trust in the symbolic scaffolding of modern life. Without trust, society slides deeper into psychotic imaginings: conspiracies, scapegoating, and apocalyptic narratives.

Wars as rituals of nightmare

War is the most literal manifestation of collective nightmare. Nations no longer simply defend borders. They defend stories of identity, superiority, and destiny. Every bomb is not only a military act but also a symbolic act, a re-enactment of ancient archetypes of vengeance and destruction.

Wars in the present moment, whether in Eastern Europe, the Middle East, or elsewhere, are fought with religious undertones, mythic scripts, and apocalyptic rhetoric. This is not new, but what is new is the speed and scale at which the nightmare is shared. Social media makes every war a theater of spiritual psychosis, where symbols spread faster than bullets.

The loss of symbolic balance

Healthy societies balance their symbolic structures: hope alongside fear, myth alongside reason, order alongside chaos. But when imbalance takes over, when fear becomes the only dominant note, the symbolic system itself becomes unstable. This instability mirrors clinical psychosis, where the individual loses the ability to distinguish between imagination and reality.

At the collective level, this means societies lose the ability to distinguish between fear-driven fantasy and grounded reality. Policy becomes reactive, art becomes nihilistic, and religion becomes apocalyptic. The dream of reality itself fractures into competing hallucinations.

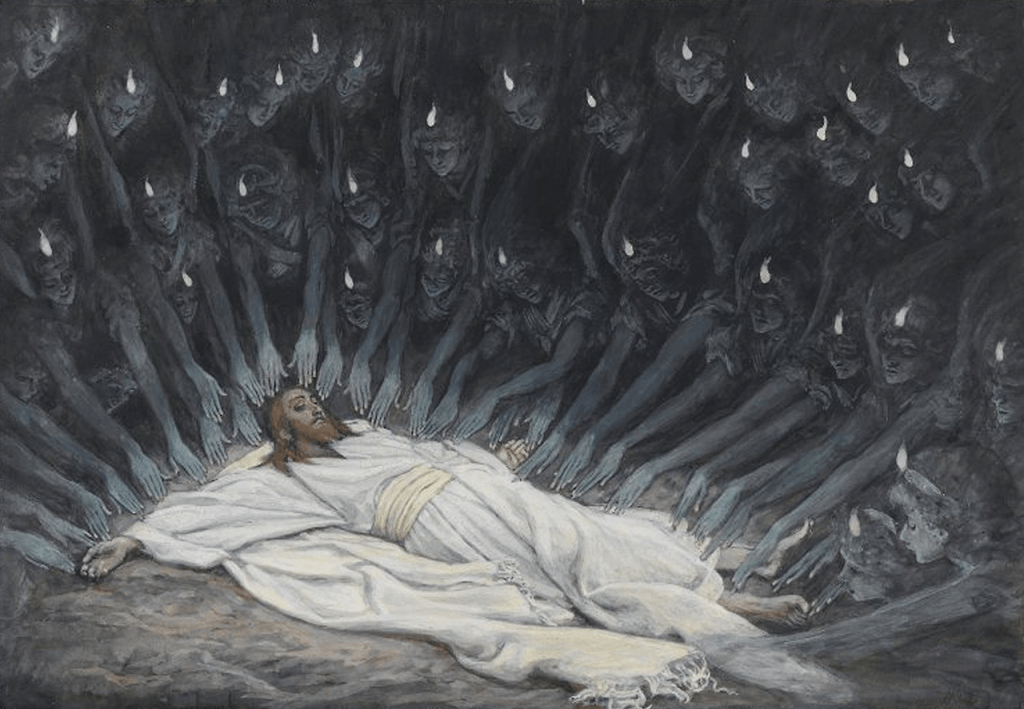

Breaking the cycle: re-dreaming reality

If the diagnosis is spiritual psychosis, the cure lies in re-dreaming. Just as individuals can reshape their inner narratives through therapy, meditation, or art, societies can reshape collective imagination. This requires new myths, not escapist fantasies, but narratives of resilience, integration, and healing.

Art, spirituality, and even technology can be redirected. Instead of AI amplifying paranoia, it could amplify compassion. Instead of religion feeding apocalypse, it could feed reconciliation. Instead of economies anchored in fear, they could be rooted in trust, reciprocity, and shared stewardship.

The task is not to wake up from the dream, but to change its texture. To shift imagination from paranoia to possibility. To recognize that reality is never raw fact, but always partly dream, and that we have the power to dream otherwise.

We stand at a precipice where collective imagination leans heavily toward the abyss. Wars, instability, and technological feedback loops threaten to make the nightmare permanent. Yet the very fact that imagination shapes reality is also a source of hope. If our nightmares can become real, so can our visions.

The challenge is whether we remain trapped in spiritual psychosis, or whether we find the courage to imagine a reality that heals rather than destroys. The dark dream is not inevitable. But resisting it requires radical honesty about the depth of our delusions, and radical creativity in forging new symbolic paths.

Join my Pateron here.