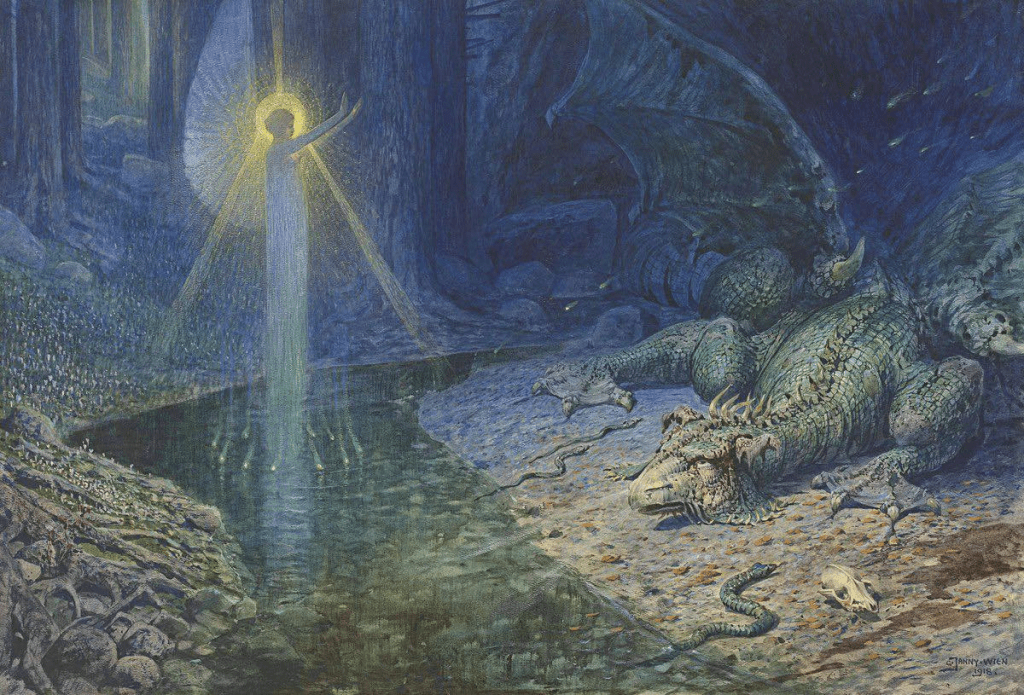

Medium/size: pen & black ink, pencil, watercolor and bodycolor (gouache), heightened with gold, on paper; ~60 × 88 cm. Signed “G. Janny – Wien/1918”; verso inscribed with the moral: “Das Gute & das Böse” (“Good & Evil”). Provenance includes Sotheby’s London, 24 Nov 1988, lot 708.

Artist background: Austrian painter and stage designer trained/worked in the famed Brioschi–Kautsky studios; he moved between Alpine landscapes and fantastical scenes in the orbit of Böcklin/Doré.

The scene, decoded

Janny opposes two regimes of power:

- Spiritual/transformative: the haloed figure that rises (literally) out of water—light, verticals, translucency.

- Coercive/brute: the slumped dragon and its brood of snakes—weight, horizontals, opacity.

Water = threshold (baptism, rebirth, access point). Cave = chthonic interior (the unconscious, the underworld). The beam crosses the pool, projecting an oblique cross that visually “pins” the dragon—symbolic subjugation without gore. Call it victory by illumination, not decapitation. (The verso title makes the ethical framing explicit.)

Composition & stagecraft (where his theater chops show)

- Blocking and diagonals: A primary diagonal runs from the upper-left light source to the dragon’s mass at lower right; the reflection in the pool creates a counter-diagonal. These two lines make a tilted cross that stabilizes the whole scene while dramatizing conflict.

- Lighting design: It’s a spotlight, not generic moonlight. The beam has a crisp falloff and a controlled “pool” (pun intended) that isolates the protagonist—the exact grammar of stage illumination Janny knew from the opera house.

- Texture rhythm: slick water → smooth robe → scaly hide → gritty ground. That tactile progression turns ethics into something you can feel.

Color, material, and that gleam

Cool blue–green tonality hushes the space so the gold heightening can do its job: the nimbus and beam literally catch ambient light in the room. In person, gold leaf/paint doesn’t just depict glow; it is glow—micro-reflective. That’s why reproductions often look flatter than the real thing. (The use of gold is documented in the auction description.)

Context: Vienna, 1918

Painted as the Habsburg world collapses (armistice, republic declared in November), the piece reads as a farewell to power defined by mass and might. It doesn’t name an empire; it dissolves one, alchemizing dragon-power into a dead weight that light can cross with ease. Janny the scenographer stages not a battle, but a transition of authority—from domination to illumination. (Biographical sources confirm his scenography roots; the date and Vienna inscription anchor the timing.)

A smart compare: The Dragon’s Cave (1917)

A year earlier Janny paints The Dragon’s Cave (listed among his works). There, the reptile is architecture; here, it’s spent force. The move from sublime monster-as-landscape to post-heroic aftermath suggests a wartime shift: spectacle → reckoning.

Ways to read it (curator’s cheat sheet)

- Theological: a deus ex machina that purifies rather than slays; water as baptism, dragon as Evil subdued.

- Psychological: the conscious (beam) entering the unconscious (cave) to integrate shadow-drives (dragon/snakes).

- Political-historical: painted in Vienna 1918; a visual sermon that legitimacy comes from light (clarity, ethics), not mass (coercion).

Why it works (and avoids kitsch)

- He uses old symbols (angel/dragon) with modern theater grammar (hard spot, blocking, set-like cave).

- The tactile dialectic—wet vs. scaly—grounds lofty allegory in bodies and surfaces.

- The gold is not a gimmick; it’s an optical device that recruits the viewer’s space into the painting.

Display & conservation notes (for collectors/galleries)

- Lighting: angled, not head-on; let the gold catch light without blowing highlights. 2700–3000K works well with the cool palette to keep the gold warm.

- Glazing: museum glass to control reflections so the painted “glow” stays legible.

- Label copy (120 words)—ready to use: In 1918 Vienna, as an empire dissolved, Georg Janny—painter and stage designer—composed this theater of moral forces. A haloed figure rises from a pool, its radiance crossing a cave to touch a felled dragon. The beam and its reflection form a tilted cross that pins brute power in place, while snakes curl across the ashen ground. Executed in ink, watercolor, gouache, and gold, the image leverages stage lighting’s logic: a hard spotlight isolates a protagonist; the set recedes to shadow. Janny’s allegory isn’t about conquest; it’s about replacement—coercion yielding to illumination. Signed and dated in Vienna, the work registers a historical pivot and a timeless one: authority grounded in light rather than mass.

Join my Pateron here.

Sources:

- Christie’s lot page — An Allegory of Power

- Wikimedia Commons — An Allegory of Power image entry

- Wikipedia — Georg Janny (biography)

- Chris Beetles Gallery — artist bio

- AskART — Georg Janny

- Wikimedia Commons — The Dragon’s Cave (1917) image entry

- MutualArt — An Allegory of Power (listing)

- Artvee — An Allegory of Power

- Wikimedia Commons category — 20th-century paintings of dragons

- Eclectic Light — article on Brioschi/Kautsky scene-painting tradition